I Wouldn’t Be Caught Dead

by Cecilia Bien

How does the mother tongue figure into the paternal generation of influence as a conduit to expropriation? I’m guilty of imitating language but also demanding that it submit to its or my own intentions. I’m trying to reconcile my complicity as a writer of criticism, by projecting my writer-self into the artistic position. I’m trying to reconcile my complicity as a daughter creating just enough distance between myself and my mother and my mother’s tongue, without projecting that distance onto the artist I write about here…

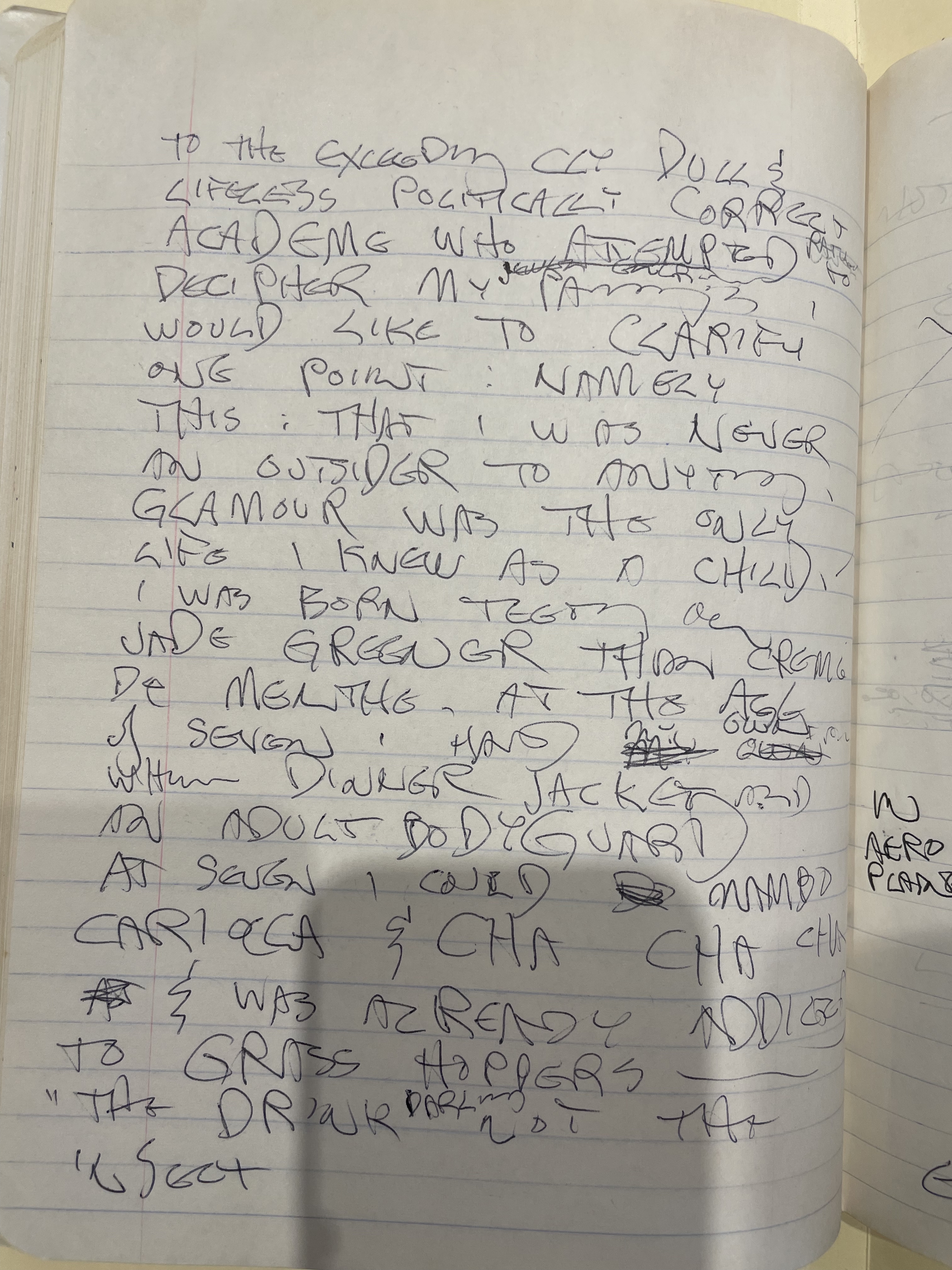

In a standard wide-ruled composition book, on saddle-stitched pages bound inside marbled black-and-white cardboard covers, Martin Wong’s ballpoint line drawings of Marie-Antoinette, Yoda, Cleopatra, and the Sphinx treat what could have been a ledger as a sketchbook. Turning the page, we’re confronted with an all-caps script, a deviation from his otherwise sharply angled M’s on tilted crutches and asymmetrical O’s with fat midsections, idiosyncratic but also practiced as if a font. In the same pen, scribbled quickly yet with precise compulsion that sustains complete legibility, he’s written, “TO THE EXCEEDINGLY DULL AND LIFELESS POLITICALLY CORRECT ACADEME WHO ATTEMPT TO DECIPHER MY PAINTINGS, I WOULD LIKE TO CLARIFY ONE POINT: NAMELY THIS: THAT I WAS NEVER AN OUTSIDER TO ANYTHING, GLAMOUR WAS THE ONLY LIFE I KNEW AS A CHILD, I WAS BORN TEETH AND JADE GREENER THAN CREME DE MENTHE.”[1]

We, the dull and lifeless politically correct academe, as Wong addresses us here, may lay claim to writing because we think there are problems to be solved. We may try to allege that our own writing practices are a method for generating a selfhood for working out our anxieties of the visual which, we think and may well argue, can be figured out through a philosophical construct made up of words. Yet, while writing, our language becomes a culprit of interpretation, innocent by association with neutrality, proven guilty when its origins are revealed within the writer's prerogative. Used as terms, disguised as descriptions, inflected by our projections, it massages our discursive imaginary of the outsider artist of whom we fetishize parts for wholes. We write to buy ourselves time to understand what we look for in our reverence to the projected real.

In the same notebook, turning two pages forward, Wong’s hand is no less urgent: “NEEDLESS TO SAY, I AM NOT NOW NOR WOULD I EVER BE CAUGHT DEAD BEING THE ASIAN AMERICAN, I RESERVE THE RIGHT TO MY ORIENTALISM. YOU ARE INVITED TO VISIT ANY TIME AT YOUR OWN EXPENSE MY FAMILY PAGODA.” The article in front of ‘Asian American’ denotes an intention for specificity, a requirement in the role of representation. ‘Oriental’ meanwhile became the politically incorrect term to describe all those who de-facto self-identified as appropriately “Asian”––blackish hair and slanty eyes. Wong’s Orientalism here was on its way to becoming neologistic for those who likewise wanted to reclaim it from its academic use, coined officially in 1978 to describe the process and structure of making a group of people and their habits adequate for study and theory.[2] For Wong, to disidentify was to disclaim a projection. So he took what theory fetishized about him and used it as raw material to appropriate, made it known that he was faking it and that the clues everyone followed and digested and used to identify him and his work were a red herring all along. “I don’t speak Chinese but I paint Chinatown,” he said. “In my Chinatown paintings I’ve used a lot of Chinese writing. I just copy it off of the signs.”

Assimilation is, after all, granted when you learn how to fake some part of yourself. In Wong’s case it meant playing the role of the outsider in someone else’s play and then disclaiming it as he did, twinkle in his eye, big grin––or at least the mask of one—till the end of his life.

We learned how to look at Wong’s paintings to produce and then insist on an identity to treat like a concept. We developed a skillset called visual analysis to help navigate a process of looking, before running to books or to the internet, and then to the page in an attempt to unpack feminist, marxist, lacanian, new historicist, deconstructionist or semiotic relevance. When all else failed or still fails, we project another alterity onto that designated subject, casting, with tacit force, the responsibility of an experience we then try to decipher, claiming to do so in the name of transgressive thinking until we realize it is our own interiority that we hoped to resolve all along. We thought we could turn to the self-taught, the untainted and unschooled outsider, unmarked by the paternal influence, for purist answers to our present. Yet in doing so we end up projecting onto the dead artist through our interpretation of his works. The persona[3] we invent as a result becomes not only a matter of conjuring a biography or realizing an intention, but also an effect of a late stage representation––that is, a representation that fulfills discursive and market functions of present day. Those no longer alive are unable to contest being on the receiving end of the status we hold them to or punish them with.

Wong’s personal library included expired how-to manuals and coffee-table travel guides. Slightly tattered slipcovers with what Greenberg called “kitsch” images on their glossy jackets have been tagged with discount price stickers from The Strand on 12th and Broadway and come with a whiff of their in-between homes in mothballed basements or attics. Faces of men made up as women smirk on the front cover of a Cantonese opera manual. A book about San Francisco showcases its crowning glory, the Golden Gate Bridge, on the outside while the inside dedicates a section to Chinatown, indulging in portraits of different generations with black-and-white photos of those who came over during the railroad boom, those living in tenements with their kids, what their kids eat for breakfast and how they play on the streets. Wong finished most of the Chinatown paintings that he is so well known for––or at least those he is identified with–– when he was at his parents’ house toward the end of his life. The photos became primary sources for filling in the gaps of his memory and experience, which enabled him to paint, in his words, a ‘tourist’s Chinatown.’ The paintings he made using them had their Euro tour after he died, and people in Berlin, Madrid, London, and Amsterdam got to see what they thought Wong saw. Ambitious deep thinkers, along with some genuine ones too, had the feeling that the time was ripe to theorize not his persona, but rather his selfhood as being irreverent or ambivalent to his identity. We asked why he didn’t participate in the collective movements of 1970s’ Chinatown. We assumed he was at odds with being into men. We called his heritage Chinese. We were confused by his cowboy shirt and then decided that analyzing the facial expression in his self-portrait would tell us why. We concluded that he was on a lifelong quest to come to terms with an identity we were eager to name.

For this writer who has likewise unlearned and then relearned how to evade being part of any club that would want her as a member, who once based her own behavior on assimilating just enough to earn candidacy in becoming one of them before narrowly escaping, she defaults to hiding behind a suspicious attitude of her own kind, as if to usurp the projections before they are cast. She creates just enough distance between herself and those presumed to be her people, knowing that one’s motherland or mother tongue inevitably gets used against itself until it is reinvented again. After all, she has always been an observer, never fully in the thing, the same way she would never really be a diasporic person no matter how often she exercised her right to flee, and not matter how much she looked like someone who could never fully claim to ‘belong’ or whatever, still always asked where she was from despite the ongoing discourses that tried to claim experiences like her own. Rather she is a descendant of a so-called ‘member of the diaspora,’ a descendant of someone from whom she could vaguely appropriate stories to fill in the blanks. It was always a reminder that she didn’t really have cultural capital of her own. Yet it is exactly this member, her mom, whom she has always been the most ashamed of. Her mom’s refugee tendencies could be read as gauche, yet she appropriated these experiences on behalf of experimenting against the influence.

To write about art without theorizing it by intention or accident, and to not write about everything outside of the formal qualities of a work offers options to write alongside or under it. Theory is foolproof until it isn’t. Dry and reliable until it’s malleable, as long as what is followed or collaged together is appropriately or approximately referenced so that we as writers might feel invincible to being misunderstood as insincere in our poetry or ambiguous through the open doors of prose. The insecurity of the mind that writes. Autofiction is at risk of overindulgence but as long as there’s a name for it there’s a justifiable standard to follow any navel gazing narrative. At best, in the end, we filter it through the automatic hand to make it ours again.

[1] The Martin Wong Papers. NYU Libraries Fales Archive Downtown Collection. MSS.102, Box 3, “Where is he Now”. 1982-1999.

[2] Here I refer to the term ‘Oriental’ as Wong’s self-description to create a tension between a controversial term used as self-identification versus the academic coinage of ‘Orientalism’ from Edward Said. Wong wrote this letter after he moved to New York in 1978, the same year Said wrote Orientalism, so whether the conflation of the terms is coincidental or intentional is unclear. If Wong is appropriating Said’s version here, his self-identification becomes self-exoticizing. “One ought to remember that all cultures impose corrections upon raw reality, changing it from free-floating objects into units of knowledge. The problem is not that conversion takes place. It is perfectly natural for the human mind to resist the assault on it of untreated strangeness; therefore cultures have always been inclined to impose complete transformations on other cultures receiving these other cultures not as they are, but for the benefit of the receiver as they ought to be.” See Edward W. Said. Orientalism. Pantheon Books, 1978.

[3] I use persona as per Hal Foster’s concept of the artistic persona as socially constructed and heavily influenced by cultural, historical, and market forces, i.e. one that is invented in order to theorize rather than the artist as an expressive individual with autonomous agency. See Hal Foster. “The Artist as Ethnographer?” in: The Traffic in Culture: Refiguring Art and Anthropology, (ed.) George E. Marcus and Michael M. J. Fischer, University of California Press, 1995, pp. 302–309.