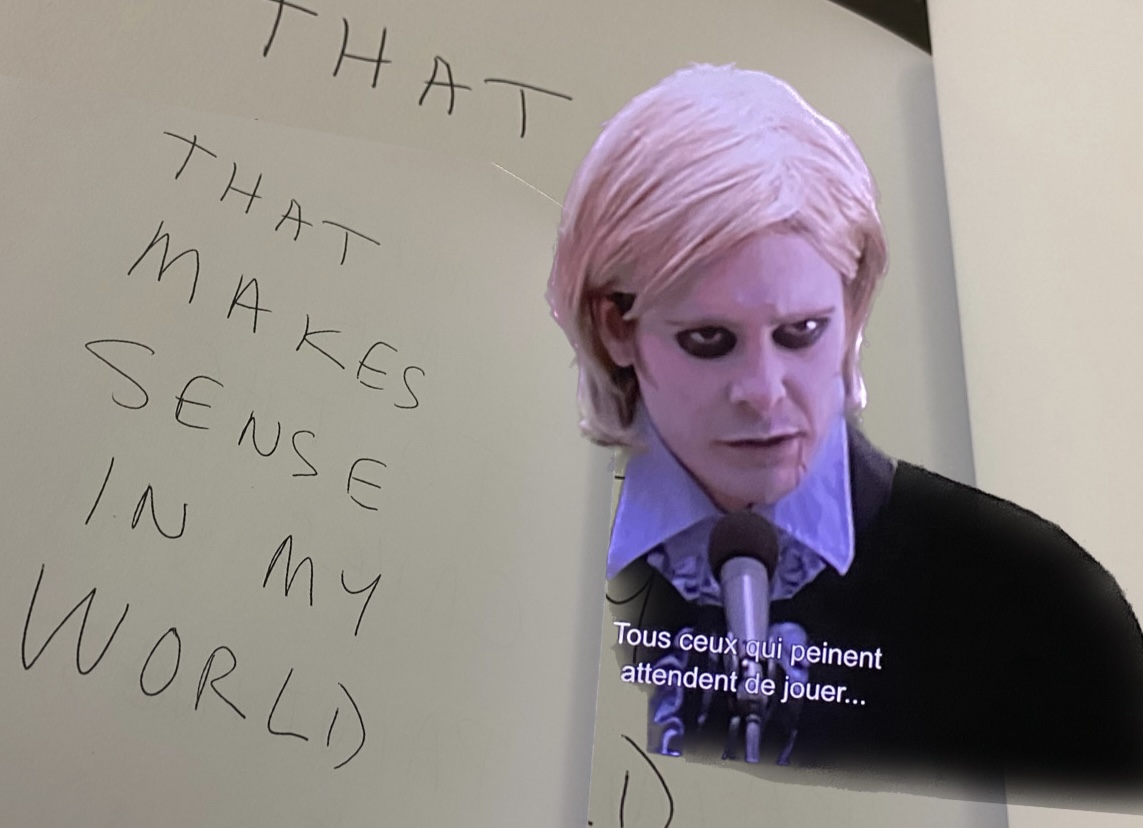

All those who struggle are waiting to play

by Luīze Nežberte

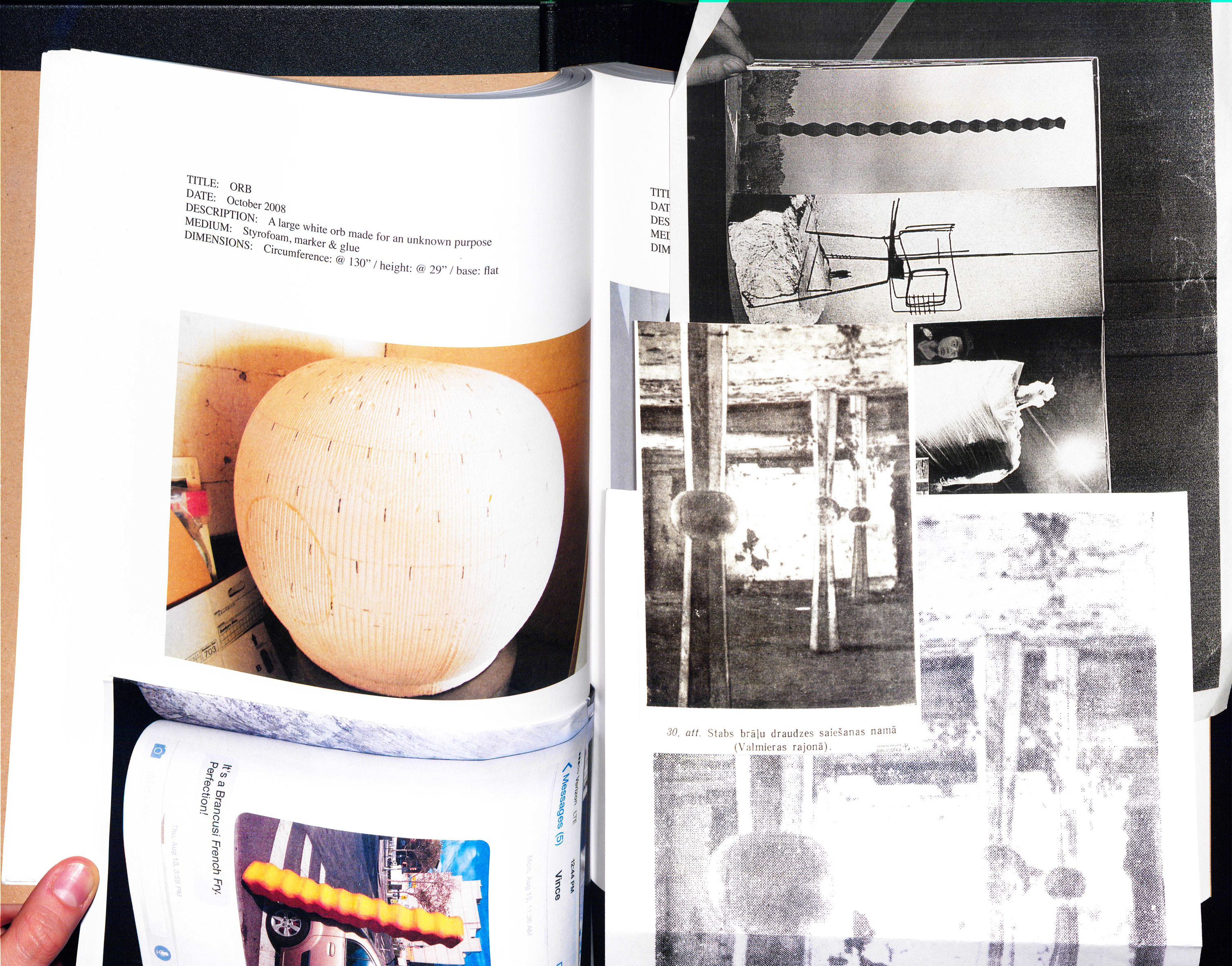

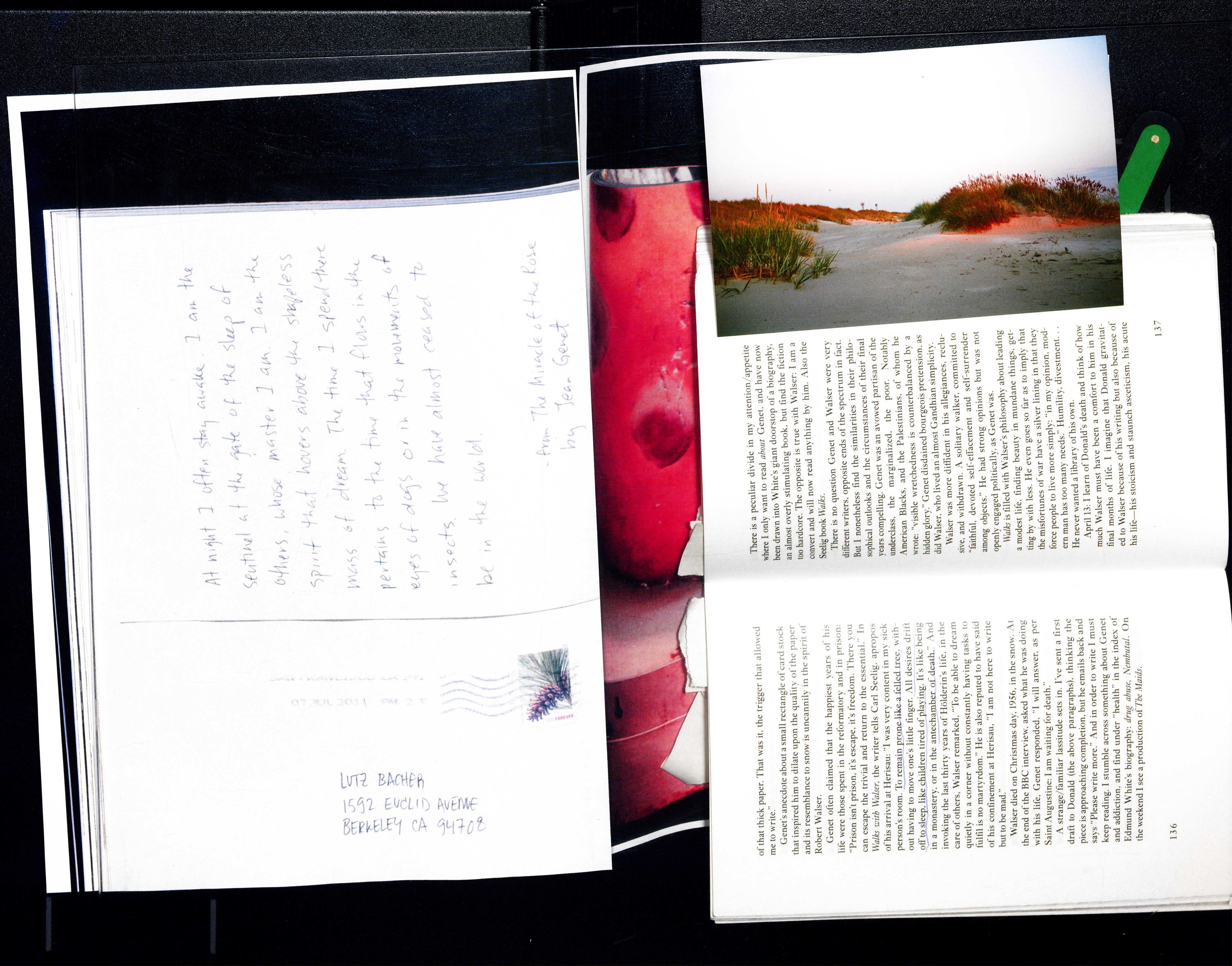

A year into psychoanalysis, I stumbled upon Index Cards by Moyra Davey— she became a vital figure to me for her writings on art, life, and literature but especially on psychoanalysis from the perspective of the analysand. Her affirmative voice created space to accept myself and my struggles in analysis, and her fragmented and referential writing encouraged me to further the question of authorship in my practice. Encountering her video work Fifty minutes in person took me to construct this text which replicates the dynamic moments of resistance that make me switch topics during my analysis sessions. Images reflecting the relation between reality and fiction, theory and identity, and the disintegration of authorship through artistic appropriation serve as associative subtitles for each paragraph. They are part of a series busy with locating a truth (or something like it) in the compilation of fragments, a coming together of artist books, novels, theory and photographs in a physical assembly underneath an overhead scanner.

It’s been hard to put this text together after months of celebrating life and trying to understand loss. I’ve ended up in a place of constant fluctuation—wishing either to be emptied out completely or filled to the brim. Everything is ambivalent on the threshold of passing time and every so often I enjoy the mute observation of life drifting further and further away from words and and I’m dismayed by how much I’ve grown to love it. Eventually, it turns into a bizarre struggle because I still believe in the tactile craving to wrap the mesh of language around the mystery of art-making and life-living and in making the effort to respond to the forms of art and life with the invisible force of language. And through all that fall in a new state of grace.

After a psychoanalysis session during which the central topic was the upcoming dreaded break in analysis because of travel, I decided to reward myself and revisit the video work Fifty Minutes by Moyra Davey on view at Sophie Tappainer.[1] While there were many things on my mind to write about, nothing felt right until I sat down on the sofa in the basement of the gallery and spent 50 minutes with the video work.

Perhaps the traditional duration of an analytical session causes a reaction in my body buidling a bridge between the alienness of time and the unconscious. Perhaps it is the opportunity of sharing the space with Moyra Davey, two dimensional and rarely looking into the camera, but still—Moyra Davey. I’m on the couch and she’s there with me.

I’ve been seeing my psychoanalyst for the past three years, the last two with a regularity of three times a week. Out of all the relationships I've had, this is the one that has lasted the longest. It is a flag I proudly wave, a person I enjoy pretending to be. It is a luxury that friends back home in Latvia have a hard time understanding. To keep up my laid-back image of a cosmopolitan emigrant, I tend to brush it off as a Viennese thing. They reply I’ve turned into a Western European.

This always shakes me to the core since in the years living abroad I went through periods of trying to morph into a Western European before I’ve learned to accept the cultural differences. My English picked up an accent that is far away from my native tongue, but there still is a hint of unease that I cannot hide and don’t want to hide anymore. When friends back home call me a Western European I realise I have become a non-belonger. By wanting to belong to the West I’ve severed ties to the East—I am away and that is being both here and there at the same time. Perpetually meandering through the endless horizons of an inferiority complex born out of a set of faulty projections that the non-belongers have on the West and vice versa. Sandra Skurvida writes that an immigrant is like a readymade— we lose our former places and functions, we dematerialise, in order to gain new meanings.[2]

Moyra makes me dream of a life (the life of a New Yorker in the 00s?) where I could roam through my unconsciousness five times a week, at the exact same time every day from Monday to Friday, and pay eight dollars for a session meaning – make the analyst pay. I see her bony body squatted and peeing behind a parked car on 155th Street. She’s thinking about Roni Horn and wondering why we can’t just piss in the park like doggies. Then she’s on the public toilet, hearing women piss like horses and dreaming of one long, uninterrupted piss. Having doubts about her impulses, she’s desperate again for a story and wondering if she is exploiting Susan Sontag as a means to an end. I am sitting in front of this text-in progress, next to me an open copy of Index Cards, and I am desperate for a story too. Occupied with forging of coincidence to have facts, detouring while assuming the possibility of exploiting Moyra for the sake of this text. Exploiting myself? Getting rid of Moyra? Getting rid of myself?

“It is a shame implying a failure of the will, lassitude, impotence. I may as well admit it. I’m blocked.”[3]

Going to the toilet is a big topic in my analysis. There was a period when every time before and after the session I would go to the toilet to have a wee. Something that started with the habit of handwashing in the times of a pandemic, turned into a sensational need of getting rid of myself and resulted in peeing out all the thoughts and desires before and all the revelations after the session. I guess that’s resistance. It’s as if something has come up from the dirty depths of my unconscious during the session and I have to get rid of it—or is it a fear of not being able to contain myself? How come nothing pours out of me when trying to write this text? I imagine myself on the deck of the ship from the film Les trois couronnes du matelot where nobody defecates, instead worms penetrate the flesh of the living to make their way out and turn into butterflies, an image of gruesomely acute pain and total relief. The butterflies don’t live for long—they get eaten by seagulls that then quickly fall to death on the deck of the ship and the sailors happily eat them. Oh, what an easy feast!

I think about the letter of invitation for this issue of dis/claim and the nature of talking openly, the love in me towards autofiction that has been growing for the last years, to be more exact—the love for honesty that makes every day life bigger and more bearable. There is the sickness of everyone trying to be good and say the right things, the world has been flattened by this niceness, and I admit to being part of this problem. Over the last weeks, even my analyst has pointed out that I use language as a tool of diversion—I craft a fog out of words that masks the truth.

Moyra has taught me to embrace what it means to create by turning to the art of others. It instilled in me a wish to document the momentary high associated with feeling seen through the words, images, gestures of another, to trace a lineage of kinship with people already passed or never encountered in person, to entrust the soft embrace of past moments built by others. Not justifying myself but borrowing and quite often very clearly stealing. Occasionally a drive to shape the history of the canon creeps in, sort of like the hand in [Philip] Guston’s painting Line—descending from the cloud like a bolt of lightning, my hand breaking through and realigning moments in time.

My analyst hypothesises that when I shoplift I fantasise about being caught, but after all these years I am still not sure. There was a time when I couldn't leave a store without taking something. First, there was a financial struggle, but later a feeling of lack on a personal level appeared which I filled with things I thought I was worthy of but couldn't afford. Then I realised I could take anything as for some strange reason people trust each other in this country, not like back at home where there is a menacing security guard at the exit of any shop. Then my meticulously kept shoplifting lists got really bizarre. Dr Haushka eye cream, 10 metres of rope, drill bits, lava salt.

Oftentimes it is easy to hide behind the word found, be it object, be it footage, because in the end found implies an accident, a giving up of agency. I do not believe in such an accident; I look for material with a focused need. Admittedly this feels wrong but something occurs when you linger in the feeling of shame and forget the absent audience: Yes, I’m busy performing acts of theft by finding in the library of the university, the museum, the gallery — in broad daylight underneath everyone’s noses.

Just like the 300 euros I desperately needed a few months ago — I looked for them and then, there they were — first a Fata Morgana in the middle of a noisy street in Berlin, but then the tangible possibility to pay for my sculptures’ transport. There was more money laying there, but I didn’t take more than I needed. Dodie Bellamy writes in her story Complicity on shoplifting: “We knew we were perverts so we wallowed in it.” I am not greedy, just a bit of an incurable criminal at heart that is struggling to admit the pervertedness of it all.

[1] Taking Notes, curated by Theresea Roessler, Sophie Tappeiner, 12.09.-14.10.2023.

[2] Sandra Skurvida:Your Time Is My Time, Milan: Mousse Publishing 2023.

[3] Moyra Davey: Index Cards. London: Fitzcarraldo Editions 2020, p.41.